Morality is a form of law that governs behavior. Nothing like opening by stating the obvious. External influences, whether institutional, cultural, or spiritual, shape our morality and guide us in knowing right from wrong. We are compelled to act by external forces then shape our responses to them either according to our value systems or altering our value systems to facilitate the expeditious action, internalizing a moral modification. It is a conundrum, like the chicken and the egg, of which comes first – behavior or values. The integration of behavior and values can cloud which holds priority and the adjustments we make in either are often all but undetectable nuances. But we also sometimes deceive ourselves, claiming certain value systems of which we hold imperfect or incomplete knowledge then act discontinuously with our claims. The result is a bifurcation of reality which results in what the Bible labels as double-mindedness, a result of spiritual immaturity and ignorance misinforming faith, of which we all are guilty by varying degrees.

One example occurs in the dis-integration of faith and economics. Technicians have appropriated economics in the last century as a science, and in a strong sense, it is in so far as it is merely formulaic for interpreting data for historic analysis and predictive modeling. But economics is also a study of moral philosophy as economic decisions involve the social contract we hold with all others affected by our decisions. Hence, we tend to think of economics in these two ways and largely in isolation. This divide in our thinking gives way to making business decisions based solely on the numbers and resorting to axioms like “It isn’t personal, it’s just business,” when it comes time to lay off workers during work slowdowns. The unemployed find their status intensely personal and it affects their entire household and external relationships that depend on their spending or giving. The ripples on a pond go a long way.

We need to understand the “two natures” of economics. The scientific one is analytical, i.e., collating data for historic understanding and predictive modeling. The moral nature is applying social value to economic decision making. We will do neither particularly well if we neglect either aspect. That is to say, if we do not understand the consequences of our actions we will make poor decisions, AND making decisions devoid of creational (including not only humankind but also the whole earth) consideration we undermine economic potential.

The study of economics throws around the phrase unintended consequences. These are the things that happen that we simply did not anticipate. These are sometime hidden effects but likely as often result from shortsightedness due to a lack of due diligence in thinking our decisions through. Unintended consequences may also come from willfully not thinking about how far the ripples will reach for fear, even if subconscious, that we will run into a conflict of values. Those conflicts tend to reside on the threshold between worldly values and heavenly values. Avoiding them excuses us from having to make hard or even (seemingly) illogical choices.

Worldly values are an interesting study which leads all the way back to Genesis 3 and Adam and Eve’s fall from grace. In the Garden of Eden, their provision was growing all around them. One suspects that in every season there was low-hanging fruit, easy to reach, ripe and ready to eat at any given moment. In perfect communion with God there was no need of sweating income statements or balance sheets. It was more like a business enjoying an eternal fast growth curve. Granted there was no downside to the provision of the Garden. There were no investors and no concern over profitability, shrinkage, market fluctuations, union strikes, or other effects which are detrimental to commercial success in our time.

The difficulty of work increased substantially after the Fall due to the curse on the ground. The weeds stole precious minerals and water from Adam’s good crops. But the greater setback came in confidence, or rather its loss, in the availability of low hanging fruit, a product of God’s goodness and abundance. Adam relied on God for his daily provision before the Fall. With that direct provision compromised, Adam had to turn to his own wit and wherewithal to provide for himself.

Then there is a long passage of time to 2012. The conflicts that we encounter in our marketplace value judgments are the result of sin, whether systemic or personal. Our culture conditions us to accept that we live in a less than perfect world with no real hope of seeing it changed. Hence, we let less than ideal circumstances “force” us into making difficult and ungodly decisions. But the power of sin in the world has been broken in Christ’s submission to the Cross. That means we have the power to make hard decisions, not according to sight but, in faith according to Truth.

By the power of Christ’s blood, we undertake a revolution countering the introduction and prevalence of sin in the world. It may seem impossible but we have the power to turn the world on its ear. Many of the economic issues we face in the world today seem insurmountable but we have the assurance, poignantly from the story of the rich young man that Jesus encountered, that “with God all things are possible” (Matthew 19:26; Mark 10:27; Luke 18:27). Do we believe that? Will we act like we believe? How can we bring the world to an economic model of godliness? The impossible can (and will) be accomplished “‘not by might nor by power, but by My Spirit,’ says the LORD of hosts” (Zechariah 4:6b).

It is time for the universal church to slay the two-headed beast of economics and re-integrate our work and stewardship (appointed to Adam–Genesis 2:15) with our relational nature, which emanates from being made in the image of God (Genesis 1:26a) and in keeping with the communal reality of Eve’s title of helpmate (Genesis 2:18). To right the economic injustice of the world’s ways will be enormously challenging, both spiritually (demanding intimidating levels of faith) and experientially (facing circumstances and decisions that challenge the culture of reason of the marketplace).

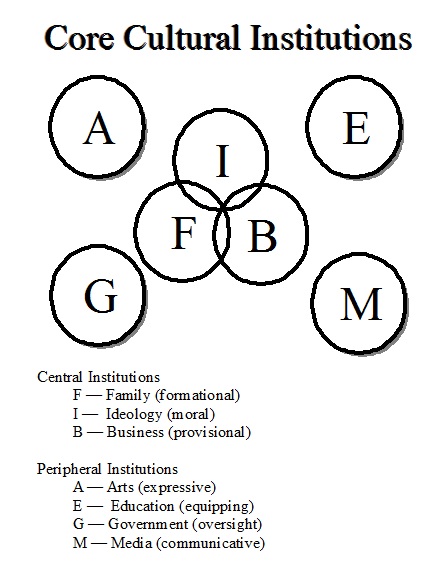

The thesis of my book, Eden’s Bridge: The Marketplace in Creation and Mission, is that the marketplace is an institution of God, implicit in the creation narrative of Genesis 1–2 and vital to the mission of God in the world. Sin has enormously corrupted God’s original economic design and the nature of righteous exchange. The hurdles that must be overcome look a lot like the giants in Canaan (Num. 13:28–31). But, “if God is for us, who is against us?” (Romans 8:31b).

Many of the assertions drawn from Scripture in this essay appear to be little more than platitudes if there is no vision of how these things may come to pass. I will discuss visioneering (to borrow gratefully from Andy Stanley) next time. Suffice it to say for now that only emboldened faith in an all-mighty and righteous God can bring the sentiment of these citations to fruition. Smith Wigglesworth, the famous Pentecostal plumber-cum-preacher, espoused a personal credo of “Just believe,” to see the miraculous of God’s power in action. Jesus did not do many miracles in His hometown due to the unbelief of the residents (Matthew 13:54–58).

The Franciscan monk, Fr. Richard Rohr wrote in his daily devotional broadcast about the lack of teaching on the transition from living under law to walking by the Spirit:

Laws serve us well at the beginning and everybody must go through this stage and internalize these values. But as Paul says, laws are only the “nursemaid” (Galatians 3:24) to get us started. The fact that we have not taught this makes me think that history, up to now, has been largely “first half of life.” (from “Living a Whole Life” daily devotional–February 4, 2012).

The fields are ripe for the harvest (Revelation 14:15e). Now is the time for our righteousness, like Father Abraham’s, arising from faith, to restore the marketplace to God’s intention, to overcome the divided minds that praise God on Sunday and worship at the altar of the world, succumbing to its deceitful intimidations, at work. The “second half” of life is at hand for the church in the marketplace. Will we step out faithfully, trusting God beyond our vision? Will we slay the two-headed economic monster? It is not a matter of “can we” but one of choosing to obey God in faith.

The research that I have conducted over the last several years leads me to believe we are about to see an outpouring of God’s Spirit in the marketplace. The next two or three decades could see a wholesale shift in how many businesses assess success. We are at the threshold of an epochal change. As Ghandi might ask, “Are you ready to be the change you want to see in the world?”

Thank You!

Thank You!