One of the hardest things for many Christians to understand is that once we “give” our life to Christ (as if God did not already own us–Psalm 24:1), how do we know what steps to follow or His plan for us or how to discern God’s will?

In the West we have largely focused in recent history on personal salvation. We are saved individually. But the Bible is clear that we are also saved into a community and into a purpose. Both are lifelong commitments that serve God, serve others, and serve ourselves.

Humankind, male and female, were created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27). As a reflection of the Trinitarian community of God, Adam was given a partner, called a helpmate (for the division of labor) and wife (for the perpetuation of the species). They had a new community in an ideal setting. Their provision was available and, by comparison to after the Fall, their work was not stressful or laborious.

The Fall, that is, Adam and Eve’s choice to disobey God, cast a pall over all of humanity and the rest of creation. Being put out of the Garden of Eden launched the largest project in the universe after creation: the mission of God. In theological parlance, that is known as the Latin missio Dei. It is what the rest of the story of the Bible is all about. Christopher Wright contends that God launched His mission with the choice of Abraham as the spiritual father through whom all nations would be blessed. But the coming of Christ, the seed of Abraham, was also the seed of Adam and Noah and every other generation that preceded him in his temporal lineage. The prophets also called Jesus the Son of David. The mission of God was in motion in the mind of God from before even creation and progressed according to His plan.

Wright has done the church and the world a great service in writing a book, simply titled The Mission of God. I promote it with the warning…it is comprehensive which means it is long, well over 500 pages. Fortunately Wright has a very readable style and the progression of the book is methodical in developing the thesis and what it means to us, as the church, as we pursue following Christ and ministering to the world.

The development of focus on personal salvation in the past century has undermined the church’s efforts in God’s grand scheme, His mission. That is not to say that personal salvation is not important. It is relevant as we each are given a new heart, a new disposition, and a new role in the world. Many of us (all of us?) are afflicted with a broad range of maladies, whether physical, economic, psychological, or emotional. Jesus Christ offers us the opportunity to overcome all that has been passed to us generationally or done to us by varying levels of our communities, whether those be impacts from dysfunction in our families, our local communities, our cultures, or the world at-large. He even grants us revitalization to overcome the inheritance of sin passed down, as like-kind progeny, all the way from Adam.

But a great deal of our personal healing comes from the realization that we are not alone. The sufferings we experience, the temptations we face, and the conditions of our lives are not uncommon. That is why Hebrews 3:13 instructs us to encourage one another daily lest we fall back into old patterns of ungodly belief and behavior. I have been burdened with my own set of issues. Many of those have been addressed and healed in Bible study, prayer, and personal discipline. Most of them have been worked out through a series of relationships with other Christians who have consoled me, encouraged me, exhorted me, even scolded me along the way.

But the greatest problem I have faced is getting over myself. This life, my “calling,” gifts and talents . . . none of them are about me per se. God has created me and invited me to join Him as a son, a title I continue to aspire to through continuing the pursuit to know God and live in obedience. Hebrews is clear that I am becoming a son of God. It is a lifelong process that, like the coming of God’s Kingdom is already-but-not-yet, sealed in eternity but playing out in temporal reality.

As I continue that pursuit and God continues to woo me toward Him, I become increasingly aware of His movement on a much grander scale than anything particularized to me or my life. God is in mission and we are invited to join in that movement. My particular role appears to have something to do with understanding what God is doing and why in the marketplace and in global culture in general.

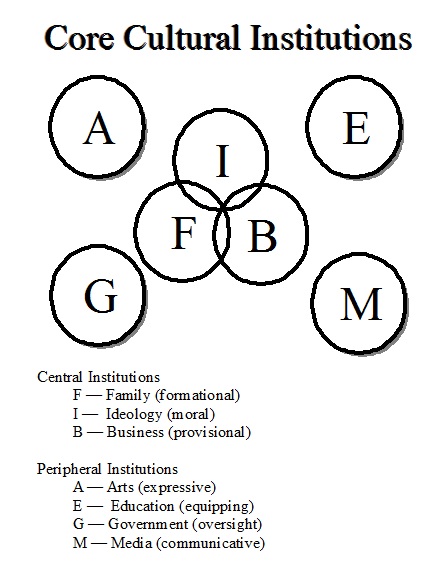

God is moving simultaneously on many fronts. Several years ago Bill Bright and some others formulated the Seven Mountains of Culture–family, church, business, arts and entertainment, government, education, and media–and launched efforts to reclaim them all for the glory of God, a torch now valiantly carried forward by Os Hillman and the Marketplace Leaders Ministries (www.reclaim7mountains.com)

God’s mission is all-encompassing, turning all of human society back toward Himself and His original plan for humankind. In the research for my book, Eden’s Bridge: The Marketplace in Creation and Mission, I reached the conclusion that all these “mountains,” except family and church, fall under the umbrella of the marketplace, where we exchange value with society beyond the household walls (natural family) or the fellowship of the church (spiritual family). Whether it is the exchange of ideas and information (education and media), opportunities for self-expression (arts and entertainment), or matters of law (government), all these contribute to establishing (for good or ill) the order and well-being of society as relational interactions. Historically these activities were largely carried out in common (shared) public spaces such as the town square, or at the city gates or the threshing floor. All these, in my mind, fall under the marketplace umbrella because they are inextricably linked in the economic formation of society.

Borrowing from Bright, Hillman, et al, I created the chart below for my own thought development. I was able to see their priority statuses of each institution given what they provide each of us. I modified the original listing, changing “church” to “ideology” because, as we encounter the world as it is, it is obvious that there are many other religions or philosophic systems that inform morality and ethics.

The three “mountains” that I classify as Central Institutions are those that were created in the natural order of the Garden of Eden–family (Adam and Eve in procreative relationship), worship (walking with God in obedience), and business (mutually beneficial exchange for communal provision).* But all seven institutions are on God’s radar in His mission of the redemption of all creation. Christian workers in all these arenas play a part in carrying that mission forward.

The challenge for the church today is to inform marketplace Christians as to their roles and responsibilities as vital to God’s mission and to release them from the false bifurcation of secular vocation and sacred calling. How does your vocation and how you do your job carry forward that movement? How do your work and work ethic reflect and glorify God? What can you do to “redeem” your industry, your workplace, your position to bring God’s Spirit, in power and truth, to bear in all the relationships touching your career?

It is a challenging question and one not easily answered but one that must be raised: when you go to work, or to the market, or to take in entertainment, or pursue education, or vote . . . are you on mission?

* For a fuller explanation of the role of the marketplace or business in Eden, see Eden’s Bridge: The Marketplace in Creation and Mission (c) David B. Doty, 2011, or the related blog post “The Vital Role of Marketplace Theology.”

Thank You!

Thank You!